Close Call: How a Tornado Chase Nearly Turned Deadly

Hello, Friend. Hope your weekend is off to a good start.

August brought some incredible storms, including the stunning tornadoes near Mound City, South Dakota, on the 28th. The storm’s structure was amazing, making me rethink the need to get too close. Honestly, keeping a distance seems smarter now, though I didn’t always feel that way.

OVer a decade ago, I loved the thrill of getting up close—sometimes too close. One chase nearly ended in disaster, filled with mistakes I only fully understood years late.

INSIDE A FUJIWHARA TORNADO

On April 13, 2012, an aggressive storm chase maneuver I made nearly went wrong. We drove north through a high-precipitation supercell near Cooperton, OK, and encountered a low-visibility tornado.

It has taken me 11 years to post this.

— Gabe Garfield (@WxGabe) December 15, 2023

On 4/13/12, an aggressive chase maneuver I made almost ended badly.

We punched north through a high-precip supercell near Cooperton, OK and saw this low visibility tornado. It didn't seem like a bad choice...

1/11 pic.twitter.com/VLagY0tYn7

I thought we were safe since the tornado appeared to be moving northeast, or at worst, east, while we were south of it. As visibility worsened, I asked my team to move closer for a better view.

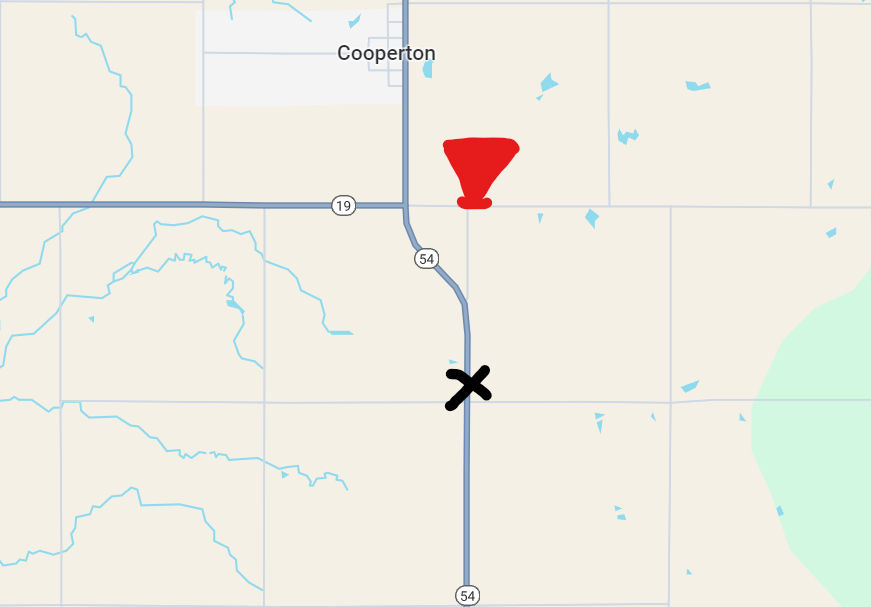

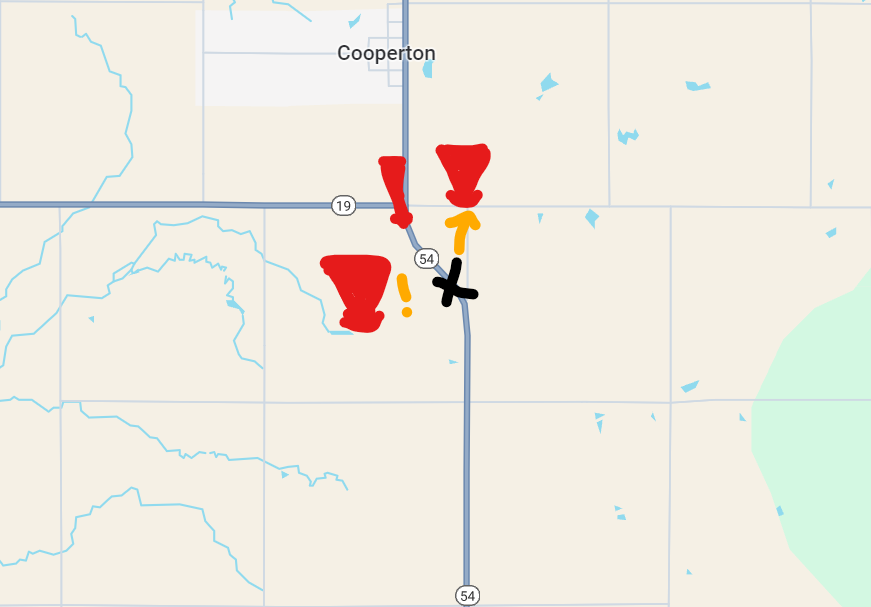

To provide some context, the first image shows what radar looked like when we entered the storm, and the second shows our position relative to the tornado. A key factor in our decision was that the storm wasn’t tornado-warned when we began. Moments later, it was.

We soon realized the tornado wasn't entirely east of the road as we had assumed. This was confusing, as it didn't match what I expected. Seeing other chasers ahead gave us some comfort, so we continued north.

However, rain began to enclose us, and we grew uneasy. My friend noticed others were leaving and suggested we do the same. I hesitated but eventually agreed. As we turned around, we spotted a satellite tornado just to our north.

Rain began to enshroud us. We were becoming increasingly uncomfortable with our location.

— Gabe Garfield (@WxGabe) December 15, 2023

My buddy noted that others were getting out of there. He suggested we get out of there. I reluctantly agreed.

We could see a satellite tornado just to our north.

5/11 pic.twitter.com/XQRSZ1ANjo

Then, I saw a tornado to our southwest. It was time to move—and fast. A massive tornado was right next to us.

As soon as we wheeled around, I realized there was a tornado to our *southwest*.

— Gabe Garfield (@WxGabe) December 15, 2023

Time to move. Fast.

A *huge* tornado was right next to us.

6/11 pic.twitter.com/CmauN2f4G6

Here's a map showing the approximate locations of all three tornadoes.

Based on KFDR's base velocity at 7:35 PM CDT, it seems like there was a tornado cyclone-scale Fujiwhara event, and we were caught in the center. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fujiwhara_effect…

Looking back, I made several mistakes:

- I was too aggressive in my positioning—chasing great footage can be dangerous.

- I didn't take our escape route as soon as we lost situational awareness.

- We relied too much on the actions of others. Safety is our own responsibility.

This happened a year before El Reno. I wish I could say this experience changed me right away, but it didn’t. It was the events of May 31, 2013, that finally made me reconsider my approach.

CHASE TIP OF THE MONTH

As the story shows, it's important to plan your storm escape route in advance. A good route takes you directly away from the tornado's path and is free of obstacles.

It's also crucial to know when to use your escape route. Mentally noting what should trigger your exit will help you act quickly in dangerous situations. Relying on the crowd for cues can waste valuable time.

TORNADO SCIENCE MINUTE

The most violent tornadoes can have winds over 300 mph, and they could theoretically be even stronger. Vortex breakdown science helps explain why.

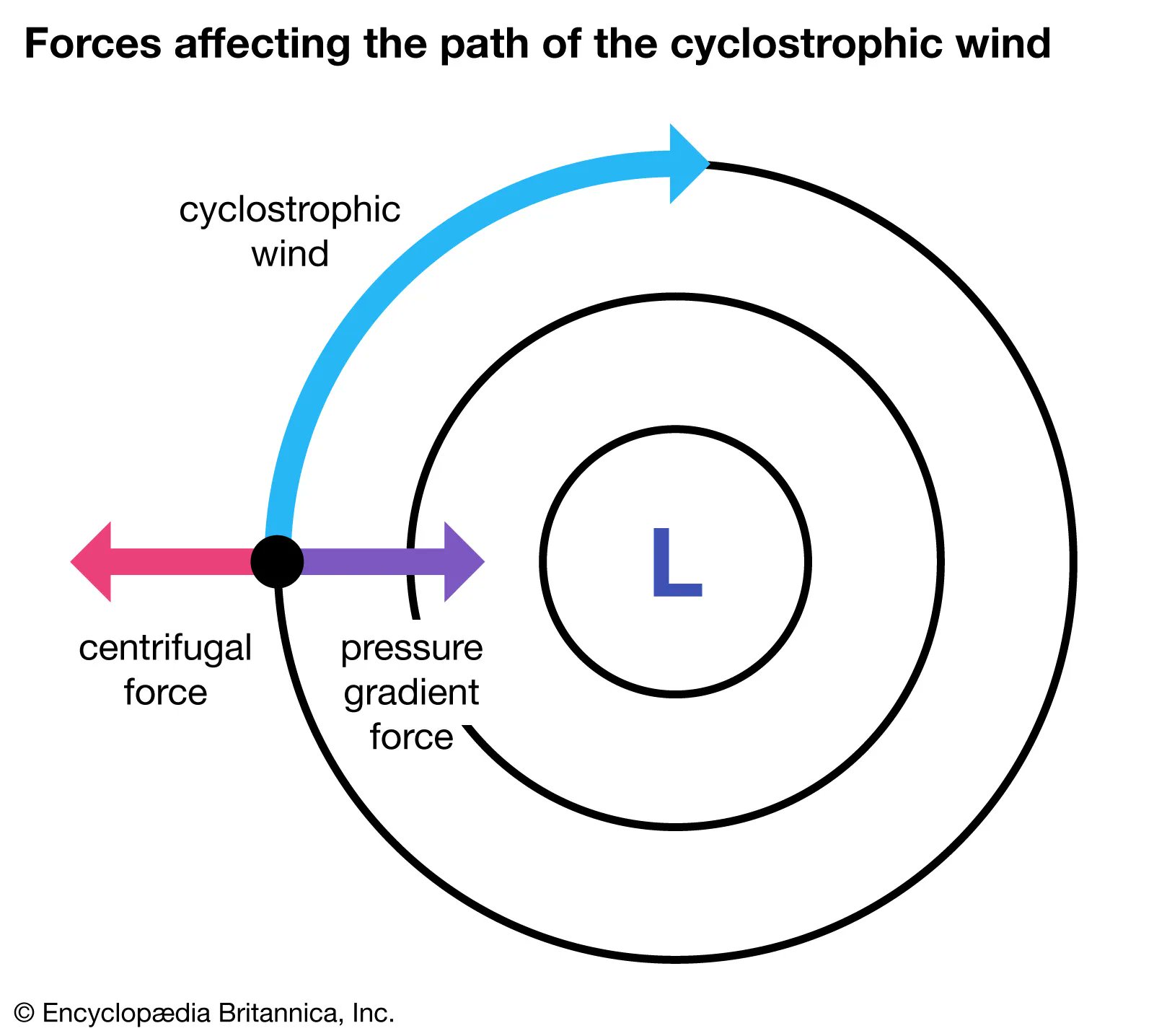

Tornadoes are typically in cyclostrophic balance, where two forces—pressure gradient and centrifugal force—compete. The pressure gradient pushes air from high to low pressure, while centrifugal force pulls it outward.

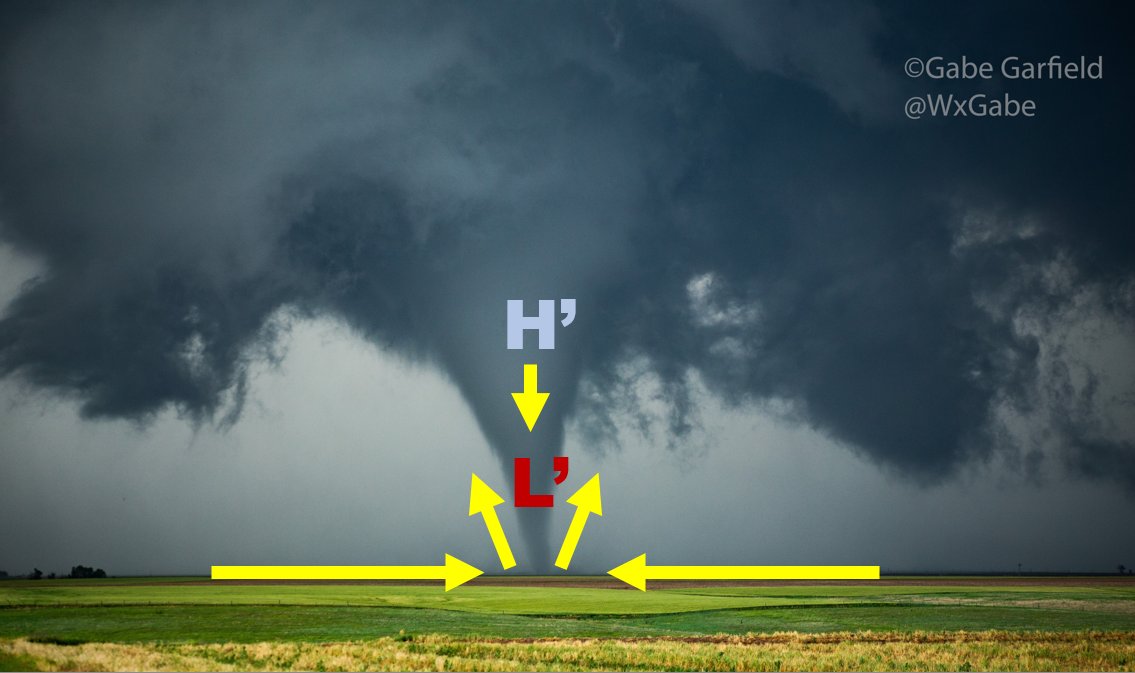

However, near the surface, friction disrupts this balance, causing more air to move toward the tornado center, resulting in a violent updraft called the "corner flow."

This updraft creates a low-pressure zone near the surface, and a downdraft may form above. If strong enough, this forms a "supercritical" vortex, where the tornado is at its strongest. As the downdraft hits the surface, it creates multiple vortices around the tornado center. These vortices can be extremely destructive, explaining why tornado damage can vary greatly from one spot to another.

___________

Well, that's all for now. Hope you enjoyed it!

- Gabe Garfield

WxGabe on X/YouTube/Facebook/Instagram